The Witch Trials- Fear, Hysteria, and Power in Early Modern Europe

The Witch Trials: Fear, Hysteria, and Power in Early Modern Europe

Few chapters of European history are as chilling as the witch trials that swept across the continent between the 15th and 18th centuries. Tens of thousands of people, most of them women, were accused of witchcraft, subjected to brutal interrogations, and often executed. These trials were not simply about superstition. They reflected deep anxieties about religion, politics, gender, and power in a rapidly changing world. By examining how hysteria spread and why accusations took root, we can better understand the forces that fueled one of history’s darkest obsessions.

The Roots of Witch Beliefs

Belief in magic and witchcraft had existed in Europe long before the infamous witch hunts. In medieval villages, people often turned to local healers, midwives, or wise folk for remedies and charms. The Church generally tolerated such practices, dismissing them as superstition rather than heresy.

But as Europe entered the early modern era, attitudes shifted. The late Middle Ages brought waves of famine, plague, and war. The Black Death in the 14th century killed millions, leaving societies scarred and searching for explanations. In this atmosphere of fear, accusations of witchcraft became a way to explain misfortune. A failed harvest, sudden illness, or unexpected death could all be blamed on a neighbor thought to have sinister powers.

Religious change also played a role. The Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation heightened anxieties about sin, heresy, and the devil’s influence. Church authorities on both sides sought to root out threats to their faith, and witches became a symbol of evil infiltrating Christian communities.

The Hammer of Witches

One text did more than any other to systematize the witch hunts: the Malleus Maleficarum, or “Hammer of Witches,” published in 1486 by two Dominican inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. The book argued that witches were real, dangerous, and primarily female. It outlined how to identify, interrogate, and prosecute them, blending theological reasoning with lurid imagination.

Though condemned by some church leaders, the Malleus spread widely thanks to the printing press. Its influence was enormous, shaping court procedures and embedding the idea that witchcraft was not just superstition but a diabolical conspiracy against Christendom. The book’s misogynistic tone also reinforced the association of women with witchcraft, portraying them as morally weak and easily corrupted by the devil.

Who Was Accused?

Contrary to the stereotype of witches as cloaked figures meeting in secret, those accused of witchcraft were often ordinary people. Many were older women, especially widows who lived on the margins of society. Without husbands or families to defend them, they were easy targets. Others were midwives or healers whose knowledge of herbs and childbirth aroused suspicion.

Accusations often arose from personal disputes. A quarrel with a neighbor, an unpaid debt, or even a harsh word could turn into an accusation of witchcraft if misfortune followed. Social tensions, jealousy, and resentment found expression in charges that someone had cursed crops or livestock.

While women made up the majority of the accused, men were not immune. In some regions, especially in parts of France and Germany, significant numbers of men faced trial, accused of pacts with the devil or participation in sabbaths, gatherings where witches supposedly worshipped Satan.

The Machinery of Fear

Once accused, a suspected witch faced grim odds. Trials were often stacked against the defendant, with confessions extracted under torture. Interrogators used devices such as thumbscrews, racks, and sleep deprivation to force admissions of guilt. Under such agony, many confessed to impossible crimes, such as flying on broomsticks, consorting with demons, or turning into animals.

Witch trials also relied on “spectral evidence,” where witnesses claimed to have seen the accused in visions or dreams. This kind of testimony, impossible to disprove, became a powerful tool in courtrooms.

Punishments varied but were almost always severe. Those convicted might be hanged, burned at the stake, or drowned. Public executions served as both deterrent and spectacle, reinforcing community fears and the authority of those in power.

The Spread of Witch Hunts

Witch trials were not confined to one country but spread across much of Europe. In Germany, Switzerland, and parts of France, the hunts reached their most intense levels, with entire villages consumed by panic. The Holy Roman Empire, with its patchwork of jurisdictions, was particularly fertile ground, as local lords competed to demonstrate their zeal in purging witches.

In Scotland, zealous ministers and kings such as James VI (later James I of England) fueled hunts with their obsession over witchcraft. His book Daemonologie in 1597 insisted that witches posed a grave threat to the kingdom, legitimizing trials and executions.

England saw fewer executions than continental Europe, but cases still shook communities. The infamous Matthew Hopkins, known as the “Witchfinder General,” terrorized eastern England in the 1640s, accusing hundreds of women and sending dozens to their deaths.

The hysteria even crossed the Atlantic. The Salem witch trials of 1692 in colonial Massachusetts reflected the same fears and suspicions that gripped Europe, though they occurred in a Puritan society far from the continent.

Fear and Power

The witch trials were not just about superstition; they were also about control. Authorities used them to reinforce power, whether political or religious. By prosecuting witches, rulers demonstrated their vigilance in defending order and faith. For local communities, accusations offered a way to channel anxieties and punish those who stood out.

Gender played a crucial role. Women, especially those who were poor, unmarried, or outspoken, bore the brunt of accusations. The trials reflected deep-seated fears of female independence and sexuality. To accuse a woman of witchcraft was to strip her of agency and make her a scapegoat for larger social tensions.

The Decline of the Trials

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the witch hunts began to fade. Several factors contributed to their decline.

First, skepticism grew. Enlightenment thinkers emphasized reason and evidence, questioning the existence of witches and the reliability of confessions obtained under torture. Courts gradually raised the standards of proof, making it harder to convict on vague or supernatural evidence.

Second, religious wars and political turmoil shifted priorities. Leaders no longer saw witch hunts as the best way to demonstrate authority. The rise of centralized states also curbed the local zeal that had fueled earlier panics.

Finally, ordinary people began to doubt. As more accusations spiraled out of control, communities saw the devastation wrought by endless trials. Gradually, the hysteria lost momentum. By the 18th century, large-scale witch hunts had all but ended, though isolated cases persisted.

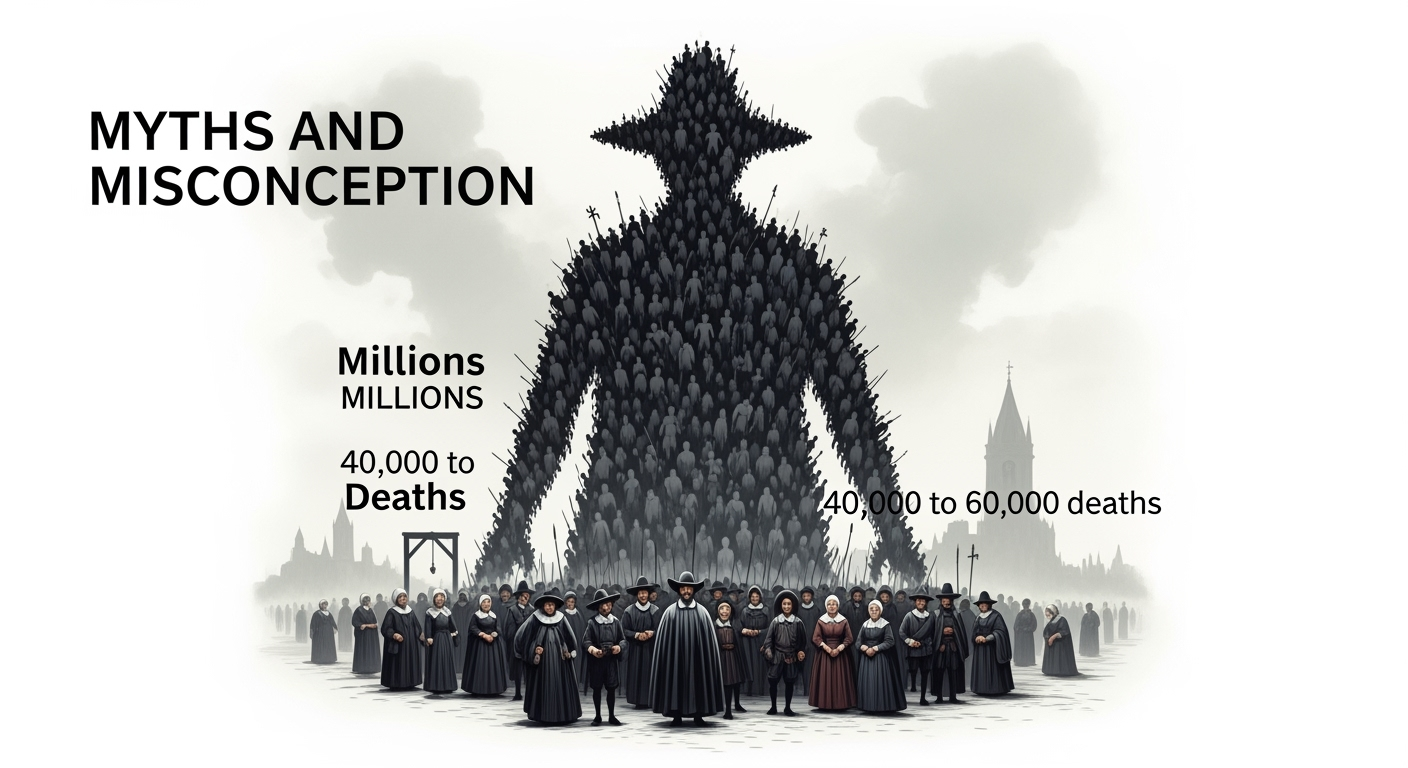

Myths and Misconceptions

The witch trials have left behind myths of their own. One common misconception is that millions of people were executed as witches. In reality, historians estimate between 40,000 and 60,000 deaths, still a horrifying number but far fewer than popular imagination suggests.

Another myth is that the Church alone drove the hunts. While church authorities played a major role, secular courts often carried out trials and executions. The hunts were the product of a complex web of religious, social, and political forces.

Legacy of the Witch Trials

Though the trials ended centuries ago, their legacy lingers. They remind us of the dangers of fear and scapegoating, of what happens when superstition and authority combine to persecute the vulnerable. They also highlight how gender and power intersected in early modern Europe, with women bearing the greatest costs.

Today, the witch trials are remembered through literature, theater, and film, from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible to modern reinterpretations that link them to themes of oppression and hysteria. They serve as cautionary tales about the fragility of justice when fear overrides reason.

The witch trials of early modern Europe were not just about imaginary pacts with the devil. They were about fear in times of crisis, the struggle for power, and the scapegoating of society’s most vulnerable. They revealed the anxieties of a world caught between medieval tradition and the dawn of modernity.

By examining them, we see not only the cruelty of the past but lessons for the present. Whenever fear and hysteria take hold, the temptation to accuse and persecute returns. The witch trials remind us of the human cost of unchecked fear—and of the importance of reason, fairness, and compassion in resisting it.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only. While HistoryReveal.com strives for accuracy, historical interpretation may vary, and readers are encouraged to consult additional sources for deeper study.