Gladiators of Rome- Brutal Truths Behind the Arena

Gladiators of Rome: Brutal Truths Behind the Arena

Few images of ancient Rome are as iconic as the gladiator. Armed with sword, trident, or net, these fighters battled before roaring crowds in arenas like the Colosseum. For many today, gladiators conjure up Hollywood visions of muscle-bound heroes shouting defiance against tyrants. Yet the reality of gladiatorial combat was both more brutal and more complex. Gladiators were slaves, prisoners, and sometimes volunteers. Their blood thrilled audiences, but their existence revealed much about Roman society, politics, and values. By peeling back the myths, we can see the brutal truths behind the arena.

Origins of the Gladiatorial Games

The idea of men fighting to the death for public entertainment may seem uniquely Roman, but gladiatorial combat likely began as a funerary ritual. The earliest records, from the 3rd century BCE, describe slaves or prisoners forced to fight at funerals of wealthy nobles, offering their blood as a tribute to the dead. Over time, what began as ritual sacrifice evolved into spectacle.

As Rome expanded, gladiatorial contests grew in scale and popularity. By the late Republic, ambitious politicians sponsored lavish games to win public favor. Julius Caesar, for example, staged massive spectacles featuring hundreds of gladiators to demonstrate his wealth and generosity. These events became a crucial tool of political power, linking bloodshed to prestige.

Who Were the Gladiators?

Gladiators were not a single type of fighter but came from diverse backgrounds. Many were slaves or prisoners of war, forced into combat against their will. Others were criminals sentenced to the arena as punishment. Some, surprisingly, were free men who volunteered, lured by the promise of fame, prize money, or the thrill of the fight.

Gladiators trained in special schools called ludi, where they lived under strict discipline. These schools, run by managers known as lanistae, provided food, medical care, and relentless training. Gladiators were valuable investments, so their owners had reason to keep them alive and fit, even while sending them into life-threatening combat.

Roman society saw gladiators with a mix of fascination and contempt. They were celebrated as celebrities, admired for their skill and courage. Yet they were also stigmatized, considered dishonorable because they shed blood for entertainment. This paradox gave gladiators a strange place in Roman culture: despised outsiders who could still inspire awe.

The Types of Gladiators

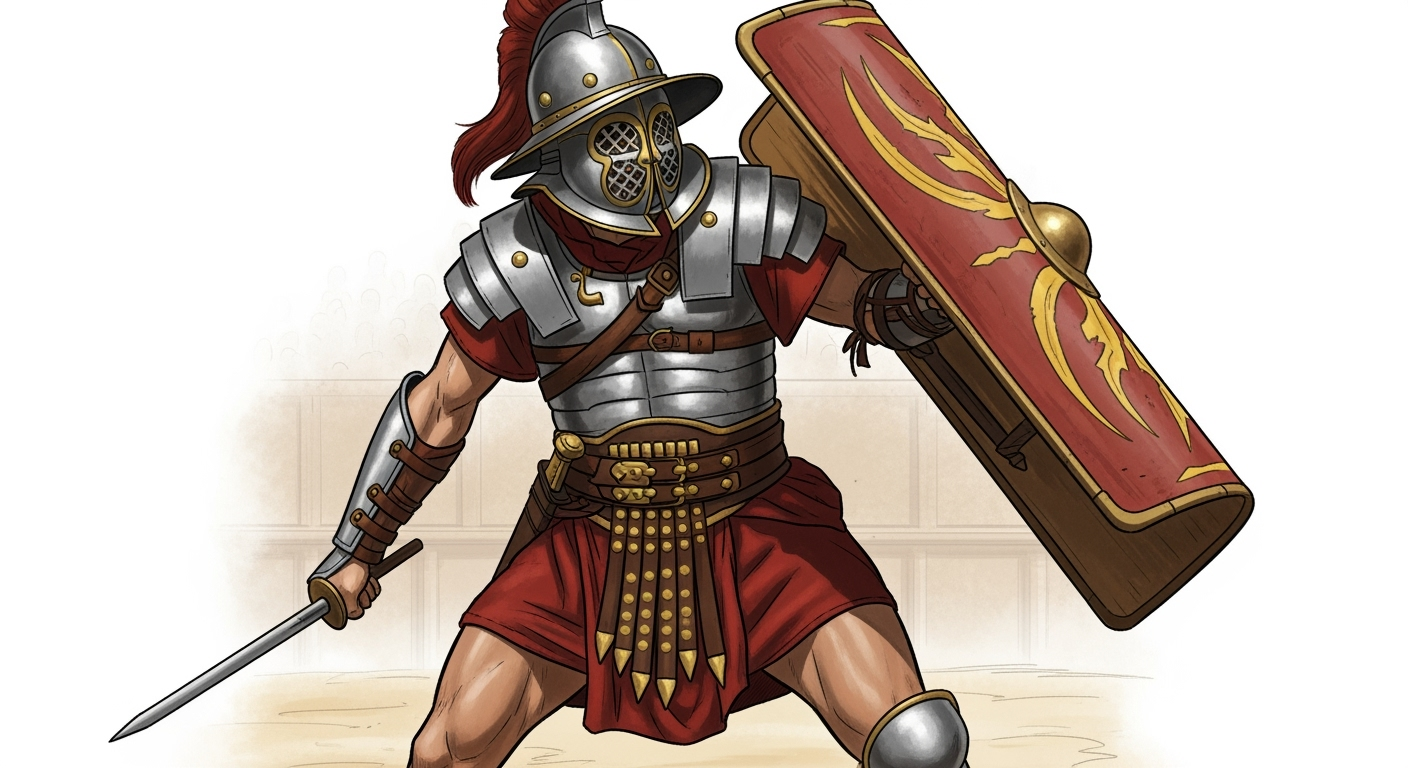

Gladiatorial combat was not chaotic free-for-all but a carefully staged performance. Different classes of gladiators, each with distinctive weapons and armor, were matched to create dramatic contrasts.

Murmillo

: Heavily armed with a short sword (gladius), a large rectangular shield, and a helmet adorned with a crest.

Thraex (Thracian)

: Wielded a curved sword (sica) and carried a small shield, often pitted against the murmillo.

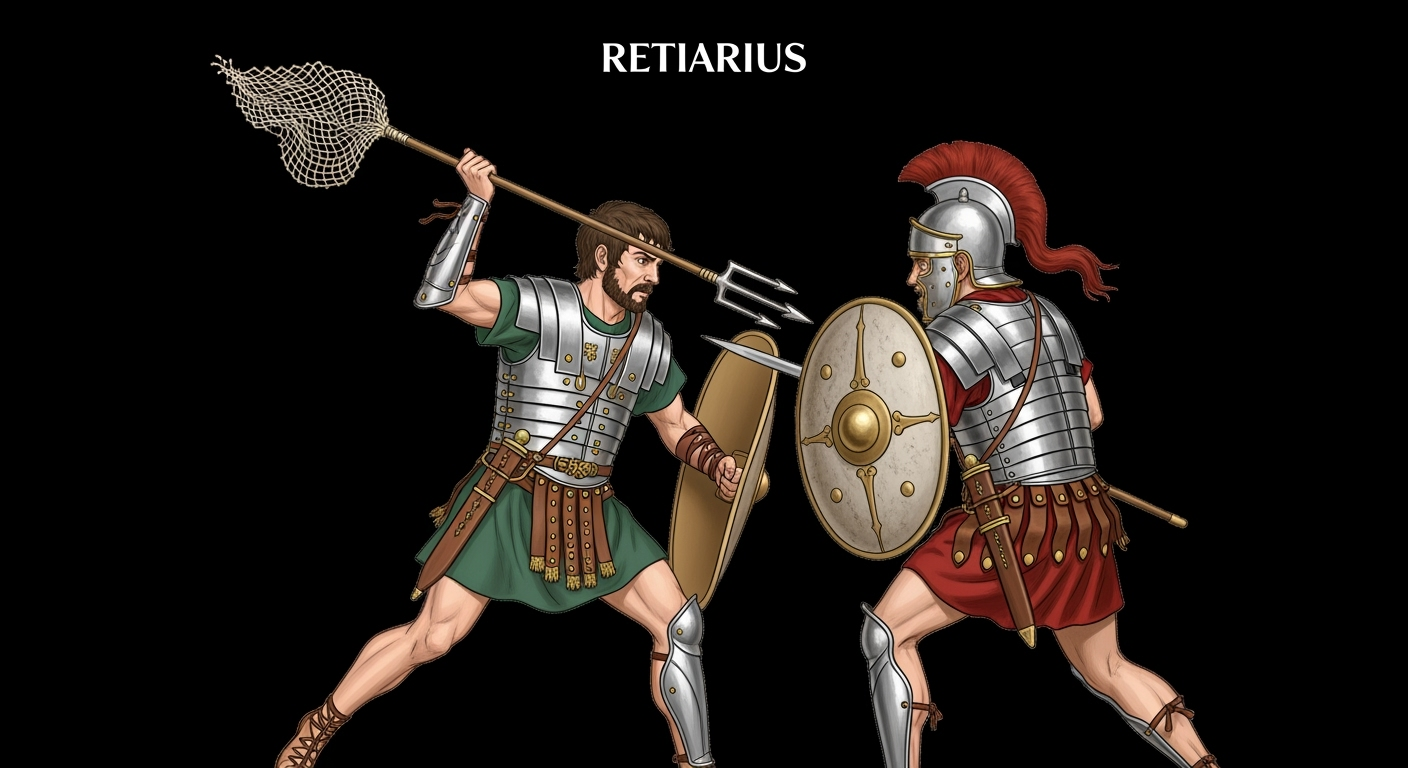

Retiarius

: Lightly armed, using a trident and net, with little armor beyond an arm guard. He relied on speed and agility, often fighting against the heavily armored secutor.

Secutor

: Specifically designed to face the retiarius, with a smooth helmet to prevent the net from snagging and a large shield for defense.

Bestiarius

: Fought wild animals such as lions, bears, and leopards, sometimes armed with little more than a spear.

These pairings emphasized contrast: light versus heavy, speed versus strength, cunning versus brute force. The goal was to create drama as much as combat.

Life in the Arena

For gladiators, the arena was both stage and battlefield. Fights took place in amphitheaters across the Roman world, with the Colosseum in Rome being the most famous. Opened in 80 CE, the Colosseum could hold around 50,000 spectators. Crowds gathered to watch not just gladiators but executions, animal hunts, and elaborate spectacles.

Despite popular belief, not every match ended in death. Gladiators were expensive, and owners had no desire to lose their investment too quickly. Many fights ended when one combatant was wounded or disarmed. At that point, the defeated gladiator could appeal to the audience or the editor (the sponsor of the games) for mercy.

The famous gesture of “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” is still debated by historians. Ancient sources suggest that the crowd or sponsor indicated whether the loser should be spared or executed. Some gladiators survived numerous battles, gaining fame and even fortune. Others were not so lucky, falling to the roar of the crowd.

The Brutality of the Games

Make no mistake: gladiatorial combat was brutal. Weapons were real, blood was spilled, and death was common enough to satisfy audiences hungry for violence. Beyond the gladiators, the arena hosted executions of criminals, who were sometimes forced to reenact myths in deadly ways, such as being burned alive as Hercules or torn apart by wild beasts.

The Romans justified this bloodshed as a display of discipline, courage, and the power of the state. For the elite, sponsoring games demonstrated generosity and authority. For the masses, it was thrilling entertainment that distracted from hardship. The violence was not hidden but celebrated, woven into the very identity of Roman public life.

Women in the Arena

While gladiators were overwhelmingly male, there is evidence that women also fought in the arena. Ancient writers mention female gladiators, called gladiatrices, though they were rare and often treated as novelties.

One inscription from Halicarnassus describes women fighting in games during the 2nd century CE. Another account by Cassius Dio mentions female gladiators performing under Emperor Domitian. While these bouts may have been less frequent, they reveal the breadth of Rome’s appetite for spectacle, where even gender norms could be challenged in the pursuit of entertainment.

Fame, Fortune, and Freedom

Despite the stigma attached to gladiators, some achieved celebrity status. Victorious fighters could win money, gifts, and the adoration of fans. Graffiti from Pompeii reveals how spectators idolized certain gladiators, writing slogans like “Celadus the Thracian makes the girls sigh.”

Occasionally, gladiators earned their freedom. Successful fighters might be awarded a wooden sword called a rudis, symbolizing their release. Some chose to continue fighting, drawn by fame and rewards. Others retired to obscurity, carrying scars as lifelong reminders of the arena.

The Decline of the Games

Gladiatorial combat lasted for centuries but eventually faded. By the 4th and 5th centuries CE, attitudes toward blood sports began to change. The spread of Christianity, which condemned the games as immoral, combined with the empire’s economic troubles, made it harder to sustain such spectacles.

In 404 CE, the emperor Honorius is said to have banned gladiatorial combat after a Christian monk named Telemachus tried to stop a fight in Rome and was killed by the crowd. Though the exact details are debated, gladiatorial games gradually disappeared as the empire declined, leaving behind ruins of arenas and echoes of cheers that once shook their walls.

Myths and Misconceptions

Popular culture has shaped how we view gladiators, but many modern images are misleading.

Not all fights were to the death.

Survival was common, especially for skilled fighters.

Gladiators were not simply slaves.

Some volunteered, chasing fame or debt relief.

They were not political rebels.

While figures like Spartacus led uprisings, most gladiators fought because they had little choice, not to challenge Rome itself.

By untangling myth from reality, we see gladiators not just as warriors but as performers caught in a brutal system of entertainment and power.

The gladiators of Rome were both victims and celebrities, brutalized for entertainment yet admired for their courage. Their battles were not mindless violence but carefully staged spectacles that reflected Roman values of strength, discipline, and dominance.

Today, the ruins of amphitheaters and the echoes of Homeric-style heroes remind us of a culture both fascinated and horrified by blood. Gladiators remain symbols of Rome’s paradox: a civilization that built roads, aqueducts, and laws, yet also cheered for death in the arena.

The brutal truths behind the arena show us that the Roman world was not just about marble temples and golden eagles. It was also about the roar of the crowd, the clash of steel, and the men and women whose lives and deaths entertained an empire.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only. While HistoryReveal.com strives for accuracy, historical interpretation may vary, and readers are encouraged to consult additional sources for deeper study.