History of Printing Press: How It Changed Communication

When Johannes Gutenberg perfected the printing press in the mid-15th century, he probably didn’t realize he was igniting one of the most transformative revolutions in human history. Before his invention, knowledge moved slowly, constrained by the painstaking work of scribes and the limited circulation of manuscripts. Afterward, ideas spread like wildfire, reshaping religion, politics, science, and culture.

The printing press didn’t just make books—it made modern society. Let’s explore how this world-changing machine emerged, how it spread, and why it remains one of the greatest inventions of all time.

The World Before Printing

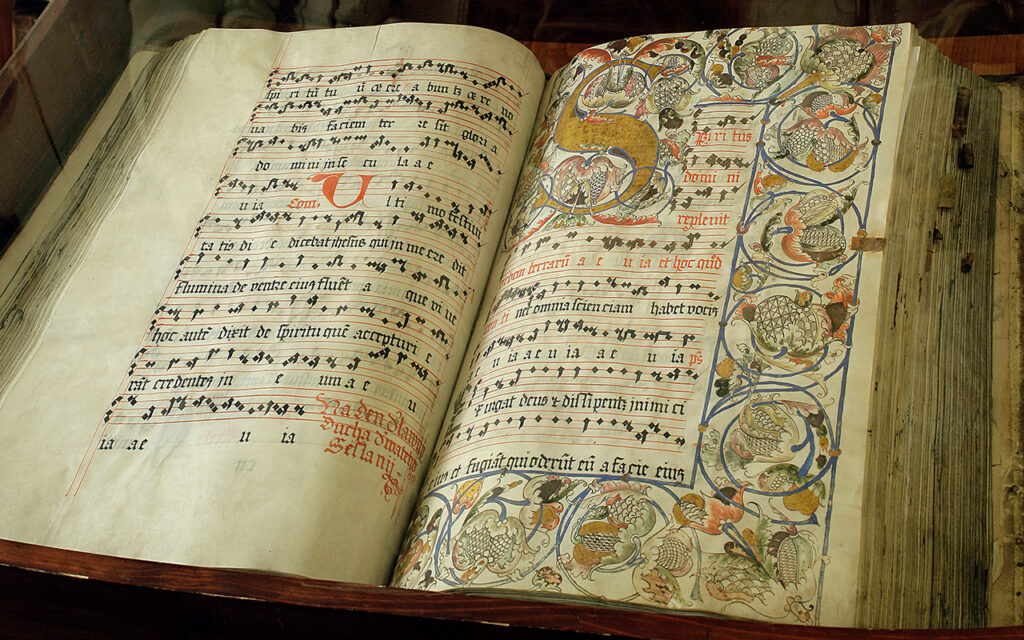

Imagine Europe in the early 1400s. Literacy rates were low, books were rare, and libraries were the preserve of monasteries and wealthy elites. Producing a single manuscript could take months or years, as monks hunched over parchment by candlelight, carefully copying line after line.

Paper existed, thanks to Chinese innovations brought westward through the Silk Road, but it was still expensive. A single book could cost as much as a small house. Ordinary people, even if they could read, rarely had access to written texts. Communication relied heavily on oral tradition and sermons.

This was a world hungry for efficiency—and the stage was set for a breakthrough.

Gutenberg’s Big Idea

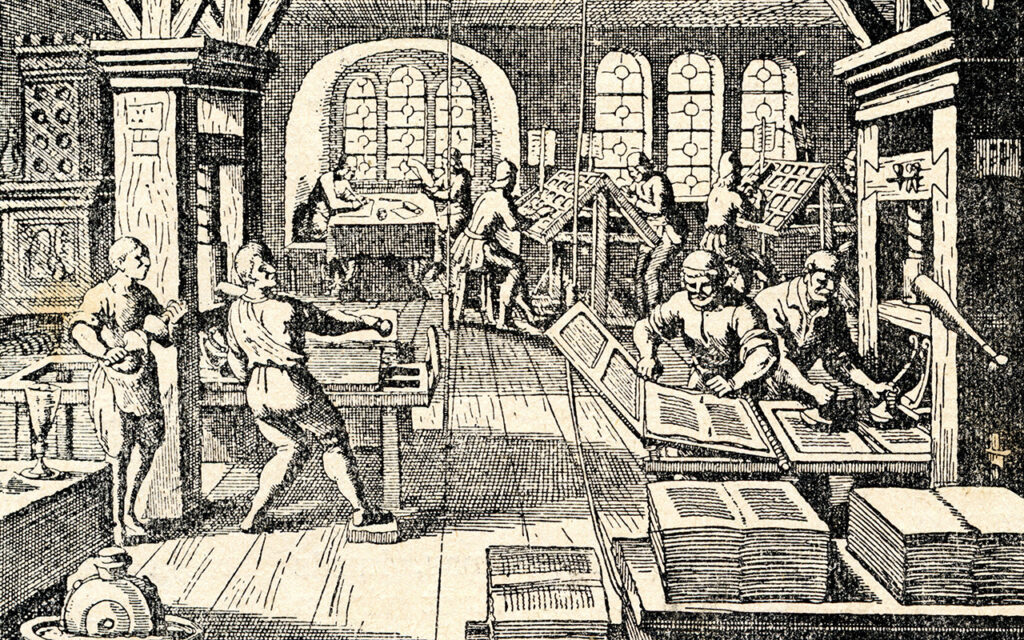

Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith from Mainz, combined several existing technologies into something groundbreaking. Movable type had been invented centuries earlier in China and Korea, but it hadn’t yet transformed Europe. Gutenberg’s genius lay in combining metal movable type, oil-based ink, and a modified wine press into one efficient system.

His press, developed around 1440, could quickly reproduce uniform letters on a page. Unlike handwritten manuscripts, every copy looked the same. Mistakes could be corrected by rearranging type rather than starting over. The process was faster, cheaper, and more reliable than anything before.

The first major product of this new system was the Gutenberg Bible, completed around 1455. With its 42 lines per page and stunning design, it proved that print could rival the artistry of handwritten manuscripts while surpassing them in volume. Roughly 180 copies were made—an unprecedented number at the time.

The Printing Press Goes Viral

Word of Gutenberg’s invention spread almost as fast as the books it produced. By 1500—just 50 years after the Gutenberg Bible—Europe had more than 200 printing presses, producing over 20 million books.

The centers of printing blossomed in cities like Venice, Paris, and London. Printing became an industry, with workshops employing typesetters, engravers, and bookbinders.

Most importantly, the cost of books plummeted. What was once a luxury item became accessible to merchants, students, and even some commoners. Literacy began to rise. Education broadened. Knowledge, once hoarded by the few, started to belong to the many.

Fueling the Renaissance and the Reformation

The timing of the printing press was perfect. Europe was entering the Renaissance, a period of renewed interest in classical learning, art, and science. Suddenly, the works of ancient authors like Aristotle, Cicero, and Galen were widely available. Artists and scholars could share techniques, discoveries, and theories more quickly than ever.

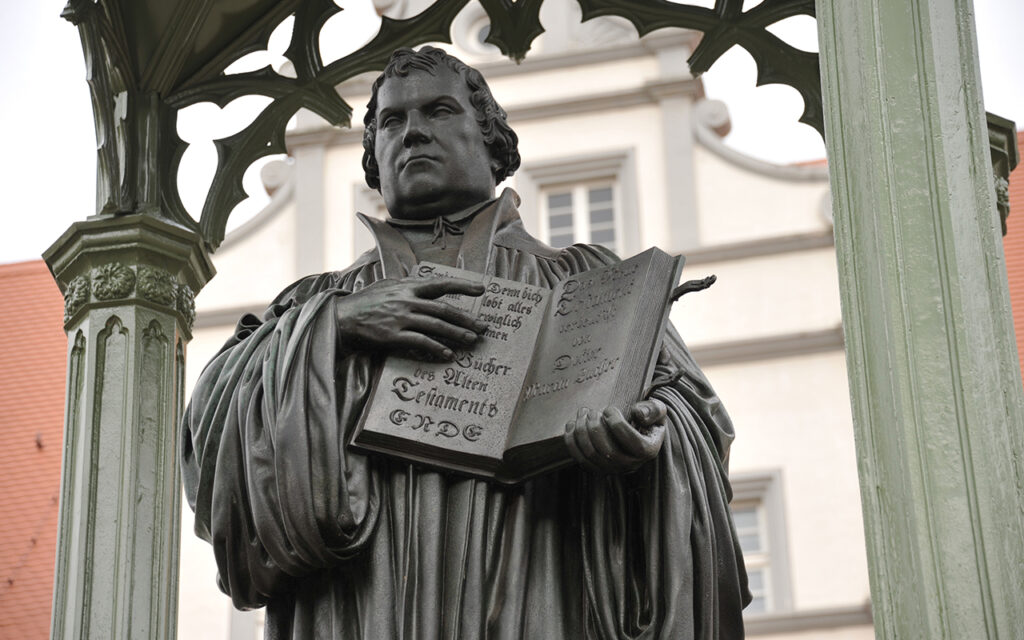

But the press also had a more explosive effect: it fueled the Protestant Reformation. When Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in 1517, it might have been a local protest. But printers quickly copied and distributed his words across Europe. Within weeks, Luther’s challenge to the Catholic Church had gone viral—16th-century style.

Pamphlets, tracts, and translated Bibles empowered ordinary people to engage directly with theology. Religious debate was no longer confined to the clergy; it was now in the hands of the masses.

Shaping Politics and Science

The press didn’t just change religion. It transformed politics and science too.

In politics, rulers used printed decrees and propaganda to reach their subjects more effectively. Revolutionary thinkers, from Thomas Paine to Voltaire, later harnessed the press to spread radical ideas that challenged monarchies and empires.

In science, the ability to reproduce and distribute diagrams, charts, and experimental results created a shared body of knowledge. Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton all relied on printed works to disseminate their theories. Scientific communities could build on each other’s work, accelerating discoveries.

The printing press helped create the concept of intellectual progress—the idea that knowledge accumulates over time and can be refined by public debate.

The Printing Press and Mass Culture

By the 17th and 18th centuries, printed newspapers emerged, giving people regular access to news beyond their immediate surroundings. This marked the birth of mass communication.

The rise of novels in the 18th century made reading not only educational but also entertaining. For the first time, people could lose themselves in fictional worlds. Print shaped culture by giving rise to celebrity authors like Daniel Defoe and Jane Austen, whose works reached wide audiences.

Long-Term Consequences

The ripple effects of Gutenberg’s press are still visible today. It created the foundation for:

- Democracy: Citizens with access to news and political ideas could demand representation.

- Scientific Advancement: Shared knowledge allowed experiments to be repeated, tested, and improved.

- Cultural Unity: Shared languages and literature helped create national identities.

- The Information Age: Every modern communication technology, from newspapers to the internet, traces its roots to the press.

The printing press was more than a machine. It was a force multiplier for human thought, amplifying voices and connecting communities in unprecedented ways.

From Ink to Digital

Of course, technology didn’t stop with Gutenberg. By the 19th century, steam-powered presses could print thousands of pages per hour. Lithography allowed for illustrations and advertisements. Later, offset printing improved quality even further.

Today, digital printing and online publishing make Gutenberg’s achievement feel almost quaint. With a smartphone, anyone can instantly share words with millions around the world. But without the 15th-century leap from scribes to presses, we might never have reached this point.

Gutenberg’s Legacy

When we scroll through social media, browse online articles, or pick up a paperback at the bookstore, we are living in the shadow of Johannes Gutenberg’s vision. His printing press shattered the barriers of communication, fueling revolutions, religions, sciences, and cultures.

In a way, Gutenberg invented not just a machine but an idea: that information should move freely, quickly, and widely. It’s hard to imagine the modern world without it.

So the next time you turn a page—whether paper or digital—spare a thought for the man who made mass communication possible. The world owes him more than we can measure.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only. While HistoryReveal.com strives for accuracy, historical interpretation may vary, and readers are encouraged to consult additional sources for deeper study.