Tracing the Plague: Black Death’s Causes and Effects in Europe

Few events in human history reshaped society as profoundly as the Black Death. Known simply as “the plague,” this devastating pandemic swept through Europe in the mid-14th century, killing millions and altering the course of history. At its height between 1347 and 1351, the Black Death claimed the lives of an estimated one-third to one-half of Europe’s population. Its causes were both biological and environmental, but its effects reached far beyond medicine. The plague transformed economies, religions, cultures, and the very structure of European society.

The Arrival of the Plague

The plague’s arrival in Europe was sudden and terrifying. It likely originated in Central Asia, traveling westward along trade routes that connected China, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. By the 1340s, the disease had spread through ports on the Black Sea and entered Europe via merchant ships. In 1347, ships docked in Sicily carrying rats infested with fleas that carried the bacterium Yersinia pestis. From there, the Black Death spread rapidly across the continent, following trade and travel routes into Italy, France, England, and beyond.

Urban centers were hit hardest. Cities such as Florence, Paris, and London saw death tolls so severe that entire neighborhoods were abandoned. The disease spread so quickly that families were sometimes unable to bury their dead, leaving corpses piled in streets or mass graves.

The Nature of the Plague

The Black Death was not a single illness but a combination of plague forms. The most common was the bubonic plague, characterized by painful swellings called buboes, usually in the groin or armpits. Victims suffered fever, chills, and weakness, often dying within days. A more deadly form was the pneumonic plague, which attacked the lungs and spread through coughing. This form could kill within 24 hours. The septicemic plague, infecting the bloodstream, was the rarest but nearly always fatal.

At the time, medieval Europeans had little understanding of disease. Many believed the plague was divine punishment for sin, while others blamed foul air, astrology, or even minority groups, who faced horrific persecution during the outbreaks. Without knowledge of bacteria or germs, doctors could offer little help beyond herbal remedies, bleeding, or prayer.

The Human Toll

The scale of death was staggering. Historians estimate that between 25 and 50 million people in Europe died during the Black Death. Entire villages were wiped out. In some regions, mortality rates reached 60 percent. The trauma left a deep psychological scar on survivors, who lived in constant fear that the plague would return.

Art and literature from the time reflected this obsession with death. Skeletons, dancing figures, and grim reapers became common motifs in paintings and manuscripts. The “Danse Macabre,” or Dance of Death, reminded audiences that mortality spared no one, from kings to peasants. The Black Death created a culture where life was fragile and death was ever-present.

Economic and Social Consequences

The massive loss of life had profound effects on Europe’s economy and society. With fewer people to work the land, labor became scarce. Serfs and peasants suddenly found themselves in a stronger position, demanding higher wages or leaving manors for better opportunities. In some cases, lords had to offer freedom or concessions to keep their workers.

This shift weakened the feudal system that had dominated medieval Europe for centuries. It accelerated the decline of serfdom and paved the way for a more mobile workforce. Cities, though devastated by disease, eventually benefited from an influx of workers seeking new lives.

Trade was disrupted in the short term, but in the long run, the reduced population increased demand for innovation. Farmers adopted more efficient methods, and artisans developed new crafts. The Black Death forced Europe to adapt, and in doing so, it laid the groundwork for future changes, including the Renaissance.

Religious Upheaval

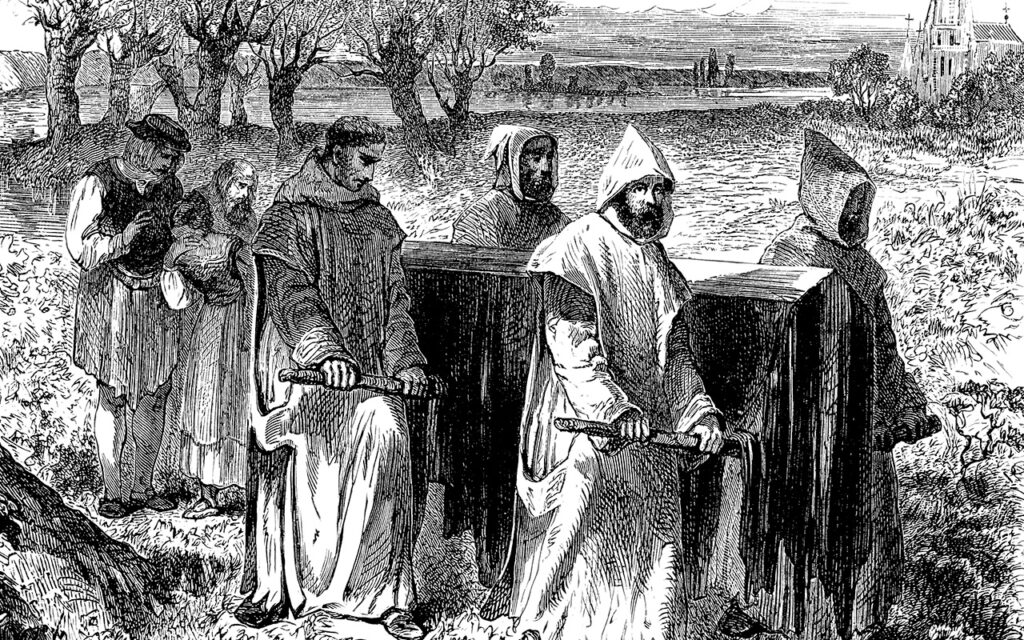

Religion played a central role in the response to the plague. Many people turned to the Church for answers and comfort. Pilgrimages, masses, and prayers were offered in hopes of divine mercy. Yet the Church’s inability to stop the spread of the plague damaged its authority. Priests and monks died in large numbers, sometimes abandoning their duties for fear of infection.

The plague also fueled movements of religious extremism. The Flagellants, groups of men who whipped themselves in public displays of penance, roamed from town to town, believing their suffering would appease God’s anger. Their processions often ended in chaos and sometimes violence against those accused of causing the plague.

Long-Term Effects

The Black Death did not disappear after 1351. Outbreaks recurred for centuries, striking Europe every few decades. While later waves were less catastrophic, they kept populations in fear and limited recovery.

Yet the long-term effects of the initial pandemic were transformative. The weakening of feudalism, combined with labor mobility, contributed to the rise of a middle class. Economic restructuring created opportunities for merchants and artisans. The demographic collapse also spurred innovations in medicine, public health, and city planning. Governments began to implement quarantines, inspect ships, and create health boards to monitor disease, early steps toward modern public health systems.

Culturally, the plague reshaped art and literature. Writers such as Giovanni Boccaccio, author of The Decameron, captured the human experience of the pandemic. The vivid realism and focus on human behavior during the crisis anticipated the more secular and individual-focused outlook of the Renaissance.

Lessons from the Black Death

The Black Death remains one of history’s most sobering reminders of human vulnerability to disease. Yet it also demonstrates resilience. Societies rebuilt, economies recovered, and cultures evolved in response to catastrophe.

Modern historians and scientists continue to study the plague not only for its historical significance but also for the biological insights it offers. DNA analysis of victims’ remains has confirmed the role of Yersinia pestis, helping researchers understand how pandemics spread and how human populations adapt.

The parallels between the Black Death and modern pandemics also offer perspective. Just as medieval Europe grappled with fear, misinformation, and social upheaval, so too does the modern world when facing global disease. The story of the plague reminds us that while science and medicine have advanced, the human experience of confronting crisis remains familiar.

By tracing the causes and effects of the Black Death, we see not only the devastation it brought but also the transformations that followed. In its wake, Europe emerged changed, with weakened feudal systems, new economic opportunities, and cultural shifts that helped lead to the Renaissance. The Black Death’s shadow was long, but its legacy was also one of adaptation and change.

HistoryReveal is your guide to understanding the past in ways that connect to the present. From ancient empires to modern movements, we bring history to life, one story at a time.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only. While HistoryReveal.com strives for accuracy, historical interpretation may vary, and readers are encouraged to consult additional sources for deeper study.