The American Civil War- Causes, Key Battles, and Aftermath

The American Civil War: Causes, Key Battles, and Aftermath

The American Civil War remains the deadliest conflict in United States history and one of the most defining events for the nation. Fought between 1861 and 1865, it pitted North against South, brother against brother, and reshaped the country’s political and social landscape. More than a clash of armies, it was a war over the future of the republic itself, testing whether a nation founded on liberty could survive half free and half enslaved. To understand its significance, we must explore the causes that set the stage, the key battles that defined its course, and the aftermath that continues to shape America today.

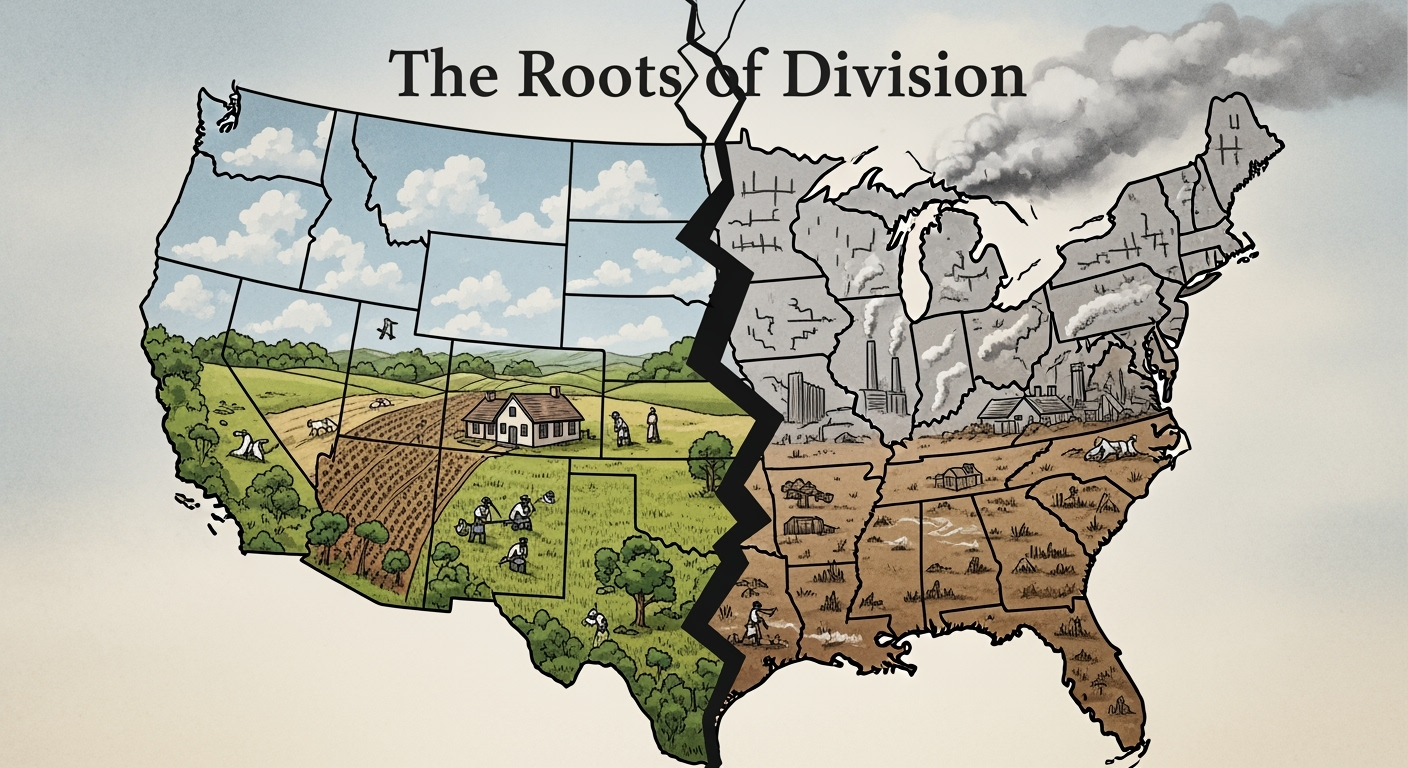

The Roots of Division

Slavery was at the heart of the conflict. For decades before the war, the United States struggled to reconcile its founding ideals with the reality that millions of African Americans remained enslaved. The South’s economy depended heavily on plantation agriculture, particularly cotton, which relied on enslaved labor. In contrast, the North was becoming more industrialized and increasingly opposed to the spread of slavery into new territories.

Political compromises had delayed an outright confrontation. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 sought to balance free and slave states. Yet each new debate over westward expansion deepened tensions. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed settlers to decide the issue of slavery by popular sovereignty, leading to violent clashes known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

The Dred Scott decision of 1857 further inflamed division when the Supreme Court ruled that African Americans could not be citizens and that Congress had no authority to ban slavery in the territories. To many Northerners, this decision signaled that the power of the slaveholding South had grown too strong.

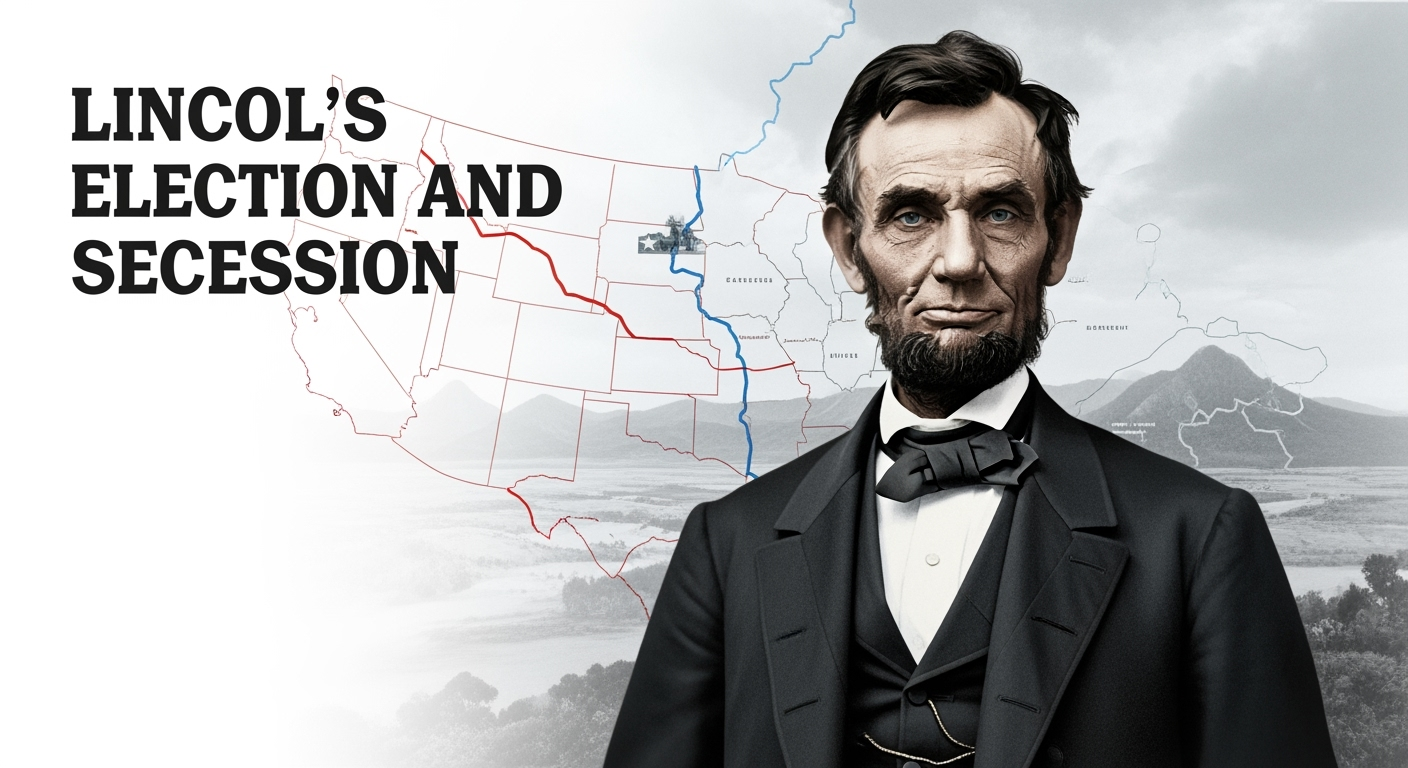

Lincoln ’ s Election and Secession

The tipping point came in 1860 with the election of Abraham Lincoln. Representing the newly formed Republican Party, Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery, though he did not initially call for its abolition where it already existed. His victory was achieved without carrying a single Southern state, convincing many in the South that their influence in the federal government was gone.

In response, South Carolina seceded from the Union in December 1860, soon followed by six more states. They formed the Confederate States of America, with Jefferson Davis as president. By the time Lincoln took office in March 1861, the Union was already fractured.

The First Shots at Fort Sumter

The war officially began in April 1861 when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, a Union-held fort in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. After hours of bombardment, the Union garrison surrendered. The attack electrified the North and solidified support for military action. Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. Four more states, including Virginia, seceded in response, bringing the Confederacy to eleven states.

Early Struggles and Turning Points

Both sides initially believed the conflict would be short. The first major battle at Bull Run in July 1861 shattered such illusions. Union forces, poorly trained and disorganized, retreated in chaos, proving the war would be long and costly.

Over the next years, the Union sought to strangle the South through a naval blockade while seizing control of the Mississippi River. The Confederacy, meanwhile, hoped to outlast Northern resolve and gain recognition from Britain and France.

One of the early turning points came in 1862 at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland. Though tactically inconclusive, it ended General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North. It also gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring enslaved people in Confederate-held territories free. This transformed the war into a fight not only to preserve the Union but also to end slavery.

Gettysburg and the High Tide of the Confederacy

In 1863, Lee launched another invasion of the North, hoping to secure a decisive victory on Union soil. The result was the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, the largest battle ever fought in North America. Over three days in July, Union and Confederate forces clashed in brutal combat. Pickett’s Charge on the final day ended in devastating losses for the Confederacy.

Gettysburg marked the turning point of the war. Coupled with the Union’s victory at Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, it left the Confederacy on the defensive. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address later that year gave voice to the broader purpose of the war, describing it as a test of whether a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” could endure.

Sherman ’ s March and the Fall of the Confederacy

By 1864, the Union had gained momentum. Ulysses S. Grant took command of all Union forces and launched a relentless campaign against Lee’s army in Virginia. Though battles such as the Wilderness and Cold Harbor were costly, Grant’s strategy of continuous engagement wore down Confederate strength.

Meanwhile, General William Tecumseh Sherman led Union forces on a campaign through Georgia, capturing Atlanta and marching to the sea. His strategy of “total war” targeted not just Confederate armies but also infrastructure and supplies, aiming to break the South’s will to fight. Sherman’s march devastated the Confederacy’s resources and morale.

By April 1865, Lee’s exhausted army could no longer resist. He surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, effectively ending the war.

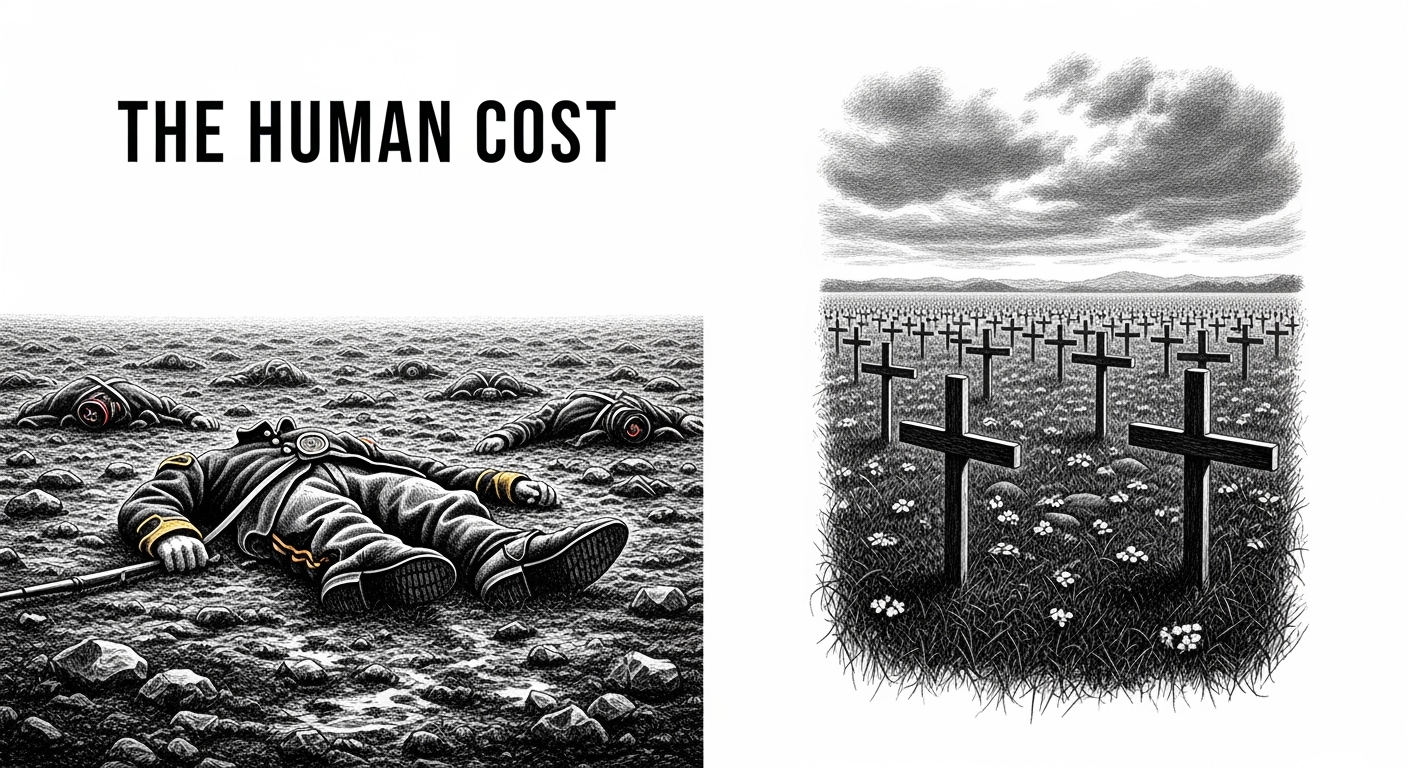

The Human Cost

The Civil War exacted a staggering toll. An estimated 620,000 to 750,000 soldiers died from combat, disease, and other causes, making it the deadliest war in American history. Millions more were wounded or displaced. Civilians, particularly in the South, suffered immense hardships from destruction, shortages, and the collapse of the economy.

Enslaved African Americans faced uncertain futures. The Emancipation Proclamation had given freedom to many, and the 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, formally abolished slavery throughout the United States. Yet freedom did not mean equality, and the struggle for civil rights would continue for generations.

Reconstruction and Aftermath

The end of the war marked the beginning of Reconstruction, an era of rebuilding and redefining the nation. The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all born in the United States, and the 15th Amendment sought to protect the right to vote regardless of race. African Americans briefly gained political power, with some elected to state legislatures and even Congress.

Resistance was fierce, however. White supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan used violence to intimidate freedmen and undermine Reconstruction governments. By the late 1870s, federal troops withdrew from the South, and many of the gains of Reconstruction were rolled back through segregation laws and disenfranchisement.

Despite setbacks, the Civil War and its aftermath reshaped the United States. It ended the institution of slavery, redefined the meaning of citizenship, and cemented the authority of the federal government over the states.

The war’s legacy endures in the ideals of freedom and unity it preserved, and in the scars it left behind. Remembering its causes, key battles, and aftermath helps us understand how a divided nation confronted its contradictions and sought, however imperfectly, to live up to its founding principles.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only. While HistoryReveal.com strives for accuracy, historical interpretation may vary, and readers are encouraged to consult additional sources for deeper study.